Notes from Black Arcadia

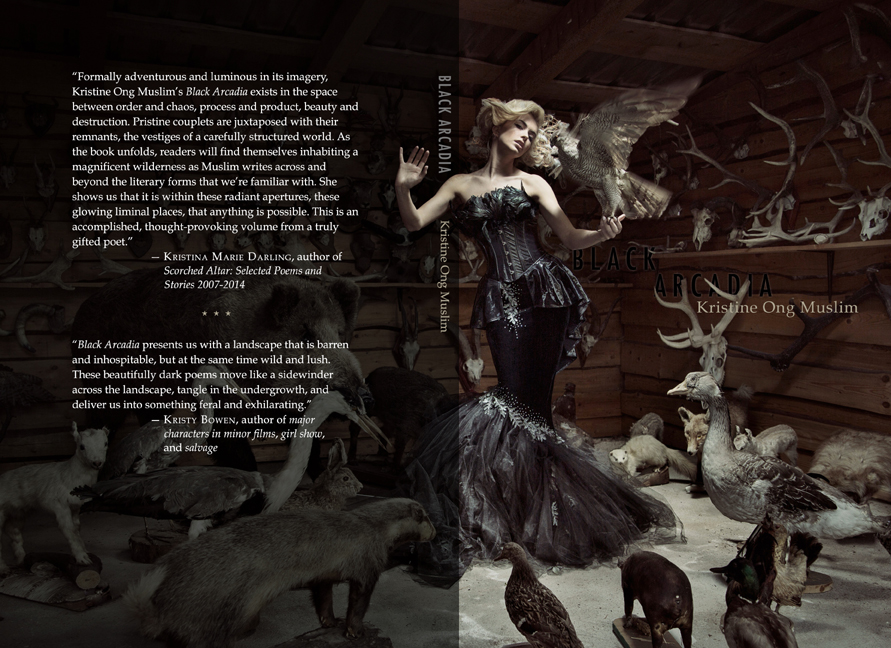

published as "Process Notes" in the poetry collection Black Arcadia (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2016)

I believe that books in mathematics are the only standalone books because their contents are not predicated on the existence of other books. Even mankind and society don’t have to exist for mathematical principles to hold true. And because Black Arcadia is not a math book, it should follow that it draws from other books. So I am writing this to serve as a rudimentary guide for reading, understanding, and enjoying Black Arcadia, as well as to disclose my sourcing methods and artistic goals.

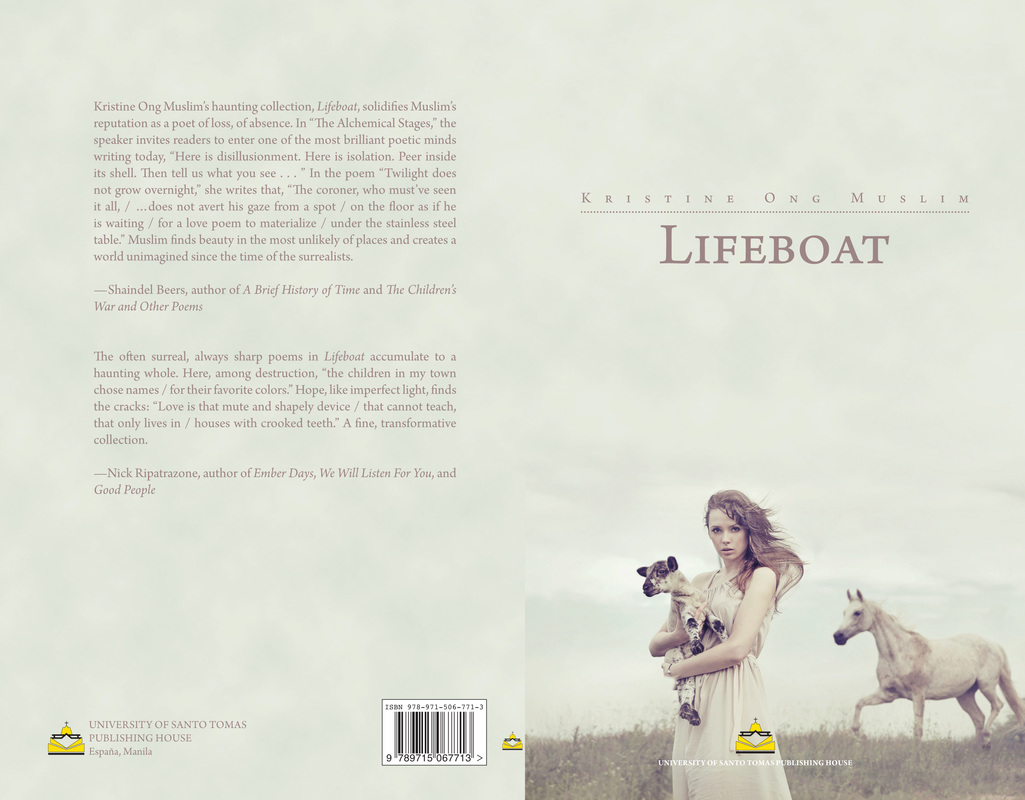

I designed Black Arcadia to be read as the disgruntled mirror image of Lifeboat, my poetry collection with the University of Santo Tomas Publishing House. Their respective covers even reflect the dialectics I am trying to establish. Arcadia can be disambiguated to refer to the dominion of the Greek god Pan but I used the term more along the line of the pure pastoral state and its ideals.

Cover art: Alessandra Hogan.

Cover art: Alessandra Hogan.

Where Black Arcadia is inquisitive and impatient in its dealings with the unexpressed and the repressed, Lifeboat fails to take umbrage at convention. Where Black Arcadia relentlessly proselytizes (as in “The Landlord,” “Blackbird,” “Buy Back,” “The Curfew,” and “The Landfall”) Lifeboat neglects to initiate the uninitiated. Black Arcadia is bloated propaganda. Hygiene-conscious Lifeboat, on the other hand, is a makeshift vessel navigating the natural environment and its otherworldly elements. Lifeboat’s concerns are easy to grasp as they generally involve pastoral stereotypes, village life, people tormented by mostly hormone-driven angst and ghostly manifestations of their guilt, people eschewing the old-world values of the quintessential rural town for those of the city. Its down-to-earth imaginings and accessibility should foil Black Arcadia’s dynamics of utopia and dystopia, of genesis and apocalypse. I only hope I succeeded in doing this.

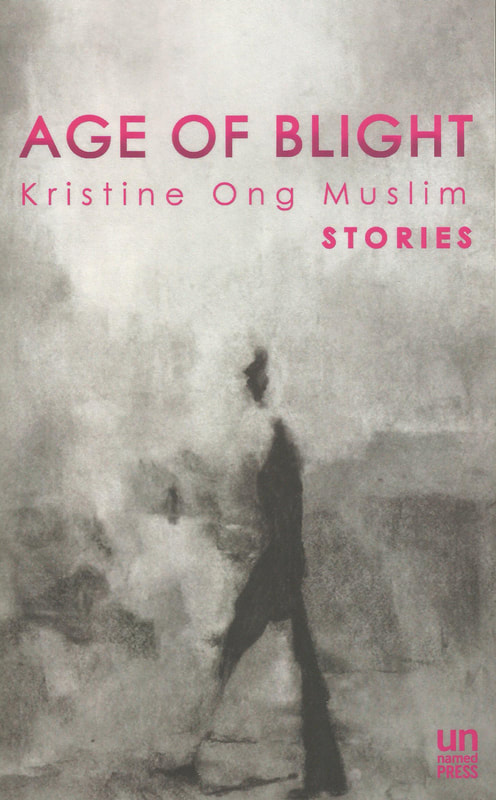

Meanwhile, Age of Blight, my short story collection with Los-Angeles-based Unnamed Press, examines in prose form some of the questions I am asking in Black Arcadia. For instance, my story on animal experimenter Harry Harlow in Age of Blight is my interrogation of the concept of absolute evil, whereas in this book, it is the poem entitled “Hunter.”

In Age of Blight, I probed the nature of the divine being, which I labeled the Great Beast in a story called “The Quarantine Tank.” The Great Beast is kept in a chamber inside a chemical manufacturing plant managed by operators in hazmat suits. In Black Arcadia, I associated the divine being with intrinsic beauty in “Bright Noise” and then castigated it in “Wildflower.”

In “The Day It Rained Fish and Swallows,” I wrote:

Meanwhile, Age of Blight, my short story collection with Los-Angeles-based Unnamed Press, examines in prose form some of the questions I am asking in Black Arcadia. For instance, my story on animal experimenter Harry Harlow in Age of Blight is my interrogation of the concept of absolute evil, whereas in this book, it is the poem entitled “Hunter.”

In Age of Blight, I probed the nature of the divine being, which I labeled the Great Beast in a story called “The Quarantine Tank.” The Great Beast is kept in a chamber inside a chemical manufacturing plant managed by operators in hazmat suits. In Black Arcadia, I associated the divine being with intrinsic beauty in “Bright Noise” and then castigated it in “Wildflower.”

In “The Day It Rained Fish and Swallows,” I wrote:

“.... a tank in the chemical plant

across your grandfather’s fields of lavender.”

The image of teeming lavender fields facing the industrial superstructure of a chemical manufacturing plant is fleshed out more fully in my “The Quarantine Tank” story in Age of Blight. In the story, older farmers pass their knowledge of cultivating lavender to the younger generation. This process never ends. But then the farmers in the lavender fields do wonder about the Great Beast (whose vague description they heard from their ancestors) that was said to be kept in the chemical manufacturing plant right across their lavender fields. In short, the farmers were wondering about the nature of the divine being. What they do when they begin to doubt its existence—that’s the stimulus for the story. This excerpt from “The Quarantine Tank” tells of the exact location of the Great Beast:

According to your elders, corners and edges present the weakest points, and weak points have no place in containers whose sole purpose is to isolate. They also say that the spherical quarantine tank is propped on a giant tripod supported by tungsten struts and that it comes with a calibrated pressure valve, eleven downstream sampling points, and a pair of fouling-resistant heat exchangers.

The quarantine tank’s drain pipe is said to lead to an inverted cone chamber housing the Great Beast.

Black Arcadia is purposely overwritten, the tone bordering on superciliousness. I did this to conjure Victorian-era steampunk, one I felt was a suitable pairing for my biomechanical constructs (lovingly styled after the creations of Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger). I reworked Cyclops, Ovid’s Minotaur, the doomsday juggernaut, the invisible man (“The Missing”), and other mythical creatures in the context of modern technology.

The Empty in “How the Empty Came for Us” is entropy in classical thermodynamics. It is also H.P. Lovecraft’s primal chaos, which is also Philip K. Dick’s Other. Most of Philip K. Dick’s stories dealt with what I sensed were his attempts to quantify and qualify his views on Hegel’s Other. PK Dick’s Other is one I’ve always read as his fixation with entropy, specifically emphasizing entropy’s kinship with the arrow of time. The poem “How the Empty Came for Us” has a story equivalent in my Age of Blight. I titled that story, “The Leech” (but was later re-titled by the publisher to “There’s No Relief as Wondrous as Seeing Yourself Intact”) to denote the all-consuming ethics of thermodynamic disorder, an entity with no concept of morality, an entity that cannot be made to choose between right and wrong.

Black Arcadia is rife with claustrophobic intrigues, which are most palpable in “The Experiment” and “The Listeners.” These recurring motifs of containment and hermetic isolation stem from how I generally perceive the outside world and its participants—an outsider looking out through a much preferred translucent and sometimes opaque window.

Jungian archetypes are used liberally in this book. The flood myth, in particular, is placed roughly in the middle of the book. “Born of Flood” is my treatment of the deluge myth. The middle section of the book is marked by a shift from second-person perspective to first-person plural, signaling Carl Jung’s collective unconscious, a now-obsolete term to denote the part of the mind that hosts our supposedly inherited memories and compulsions. First-person plural is used to signify the Self, the key archetype in an individual’s wholeness. My use of the second-person perspective—the implicit and explicit use of you—is done so that the poems can tell their own little stories, as well as dispense commands to the reader. Black Arcadia is, more or less, an instruction manual for reading archetypal events and the art of doing magic.

The opening piece, “Dear M,” is the one true cipher. To decode this book, one should have already read and internalized the second chapter of Giorgio Agamben’s Profanations, where magic and true happiness are beautifully intertwined. In childhood, you and I once desired magic. With the prompting of Walter Benjamin, Agamben deduced that our realization of our inability to perform magic and to exert supernatural powers grounds us to adulthood, to the magic-free material reality. Success in an arena where we have to work hard in order to reach our goals does not make us truly happy, according to Agamben.

Here’s an excerpt taken from “Dear M,” that prepares the reader for the rare possibility of magic.

Remember what has become of Jose of Mexico, who grew up to become the illusionist of Baghdad. He is now trembling in his pulpit of magic that preaches invisibility. Remember the radium girls whose death throes were mistaken for their drawl in the vernacular. Remember how you used to stare long enough at a figure, a form not quite there until you ultimately see something, or believe that you have seen something. You are born in the realm of Forms. Remember, remember the allegory of the cave.

The illusionist of Baghdad is a real person. His name is Jose Barrientos. The radium girls were once alive. They were twenty-something women who painted radium-laced watch dials during the 1920s. They died excruciating deaths because of the magic of not-knowing—not knowing that radioactivity kills.

Another way to read Black Arcadia is to liken its unfolding to a role-playing video game. Leveling up happens when the reader breaches the three Arcadian realms of the Underworld, the Colony, and the Prophecies. The reader as a gamer then battles the technological constructs of the artificial environment of Arcadia. Very subtly, the reader as a gamer is taught some magic tricks, given tools for divination and precognition, told to discard orthodox gods. The reader as a gamer is also reminded again and again of the archetypal parameters of his upbringing so that he develops insight about his place in society and history. In the second to the last poem in this book, the piece called “The Waiting Room,” the reader as a gamer is confronted by the near possibility of old age and terminal diseases, imparting wisdom through years of experience and acceptance of a future filled with pain. Earn the ultimate power of levitation, or to see from high up in the air all the various interlocking elements of the book, at the end of the role-playing game. In the final poem called “Levitation,” the reader as a gamer is then fully equipped to perform this.

“Imagine water and its mutable

foundation dissolving your island,

the landlocked continental mass

that houses your trespassers.

Since you are deftly angled for survival,

you too can walk on water, can float

several feet off the ground without the help

of strings, like how the ancients did it:

imbibe in its rendered form

what cannot be made whole.

Conjure what does not exist.

Conjure what cannot exist. Believe.

And you will float….”